1800-1929

The Sunset area was originally called Inlet because of a small winding stream entering the Lake at this point. Inlet, however, is a misnomer since the Lake is principally fed by springs welling from the bottom of the Lake. The original Inlet area was a large shallow basin. Bennet’s Path reached the area before 1800, and the Worthingtons settled near Inlet in 1806. But the area was generally undeveloped until 1855 when the Rhoades Hotel was opened. At this time a long wooden bridge across the Inlet basin led to a crude road over the mountain to Outlet Mills. The older mountain road was abandoned when a road along the Lake’s shoreline, from the bridge to Outlet Mills, was laid out in 1857. Settlement at Inlet was sparse although James Park purchased one hundred acres along the Old Lake Road area in 1860. The English-born James Park arrived at the Lake when he was nineteen years old. A year after his arrival, the Civil War erupted and Park joined the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery, returning to the Lake after the Civil War. A road from Idetown to the bridge, roughly the course of Old Lake Road, was laid out in 1863. At about the same time, a store was opened along the new road by A. R. Pembleton.

For many years the Inlet remained undeveloped; by 1889 a large section of the Inlet was owned by Charles and Mary Wilcox who laid the area into lots which became known as the Shawanese Plot. The area, however, would eventually attract recreational rather than cottage investors. A decided improvement occurred in 1893 when the old wooden bridge, built after the Rhoades Hotel was erected, was replaced by a long iron bridge.

Until the end of the nineteenth century, the Inlet was known primarily for the Rhoades Hotel and Lake Grove House. The area began to bloom after the advent of both the Hotel Oneonta and the trolley line in 1898. By this time the Picnic Grounds had already received a decade’s jump on the tourist trade with the construction of a Lehigh Valley Railroad branch line to Alderson in 1887.

In 1894, John B. Reynolds, who developed the trolley system on the West Side of the Valley, organized the Wilkes-Barre, Dallas and Harvey’s Lake Railway Company. The line was from Luzerne to the Inlet. In 1896, however, the trolley line was unable to secure land in Kingston Township and Dallas because of recalcitrant owners who refused to sell a right-of-way to the company. The principal opponent was Albert Lewis who had a sawmill in Dallas; he was a close business ally of the Lehigh Valley Railroad in the Back Mountain. Under state law a steam railroad, but not a trolley line, could condemn the land needed to force the line through the Back Mountain. Taking advantage of the legal quirk, Reynolds converted his trolley line to a railroad called the Wilkes-Barre and Northern Railroad Company. The new company condemned the obstructing land it needed and continued to push its line to Harvey’s Lake. Along the line it built Fernbrook Park in Dallas, and by July 4, 1897, the railroad was completed to the Inlet. From Luzerne to Dallas the Reynolds line used a small steam locomotive to pull the trolley cars. At Dallas a regular trolley pulled the passenger cars to the Lake. At the Lake the railroad company constructed a dance pavilion and picnic grounds at the end of the line on Oneonta Hill.

The Wilkes-Barre and Northern Railroad, however, was not a financial success. Since it originally was built as a trolley line, its early grades were really not suitable for heavier train traffic. The line also paralleled the mighty Lehigh Valley Railroad as far as Dallas, and the new line was unable to successfully compete with the established line for freight service. In January 1898 the railroad company decided to revert to its original design as a trolley line, which was considered more economical than a train line. A trolley line could also be expected to attract more passengers and freight traffic to the Lake. The company resumed its original name as the Wilkes-Barre, Dallas and Harvey’s Lake Railway Company and began to convert the entire line to electrical service. At the same time, several stockholders in the rail line created a company to build the Hotel Oneonta. The stunning new hotel opened in June 1898 on a site behind the Lake Grove House, which was demolished. The railway and hotel company cooperated to draw the tourist trade to the Lake, and with the popularity of the magnificent new hotel, the entire Inlet section was often popularly called Oneonta. During the summer an electrical power station was built at Luzerne, and complete conversion of the line to an electrical trolley from Luzerne to the Oneonta station was completed in late December 1898. In the early years of the trolley, the summer cars were open-sided, which provided a thrilling sightseeing ride through the lush countryside of the Back Mountain. Later, the cars were enclosed; the trolley line also served farmers who shipped produce on the line from the Back Mountain to the markets in the Valley.

The Hotel Oneonta and the trolley line stimulated the growth of the entire Inlet. In the early summer of 1897 the Wilkes-Barre and Northern Railroad opened both Fernbrook Park in Dallas and a picnic ground adjacent to its trolley station at the top of Oneonta Hill. The formal opening of the new Lake park was on Saturday, July 3, 1897, with music by the Forty Fort Cornet Band. The fare from Wilkes-Barre was thirty cents.

Little is known about the Oneonta Hill picnic grove. There was no uniform name for the park. At times it was called the “Traction Company Pavillion” while at other times it was the “Oneonta Hill Pavillion” (or “Pavilion”). The pavilion was essentially a true picnic ground, not an amusement park. It attracted family reunions and the Valley’s most recognized dance orchestras played here. For a few years around 1905 the local Camp Roosevelt Chapter of the Catholic Total Abstinence Union (C.T.A.U.) held its annual meeting at the Pavilion. The last advertised articles at the park were in May 1921. A Catholic Mass at the pavilion attracted 300 worshipers. There was no Catholic church at the time at the Lake. The last dance orchestra at the park was Macluskie’s Orchestra on Decoration Day, May 28, 1921. The pavilion was eclipsed by the New Oneonta Pavilion which opened at Sunset in 1922.

William Hill leased a substantial pavilion at the end of the iron bridge. The pavilion was probably built shortly after 1900 by Thomas Major. William Hill’s famous twin-peaked pavilion was built over the water at the Inlet basin with its front resting on a thin string of land connected to the shore. Hill’s Pavilion was almost encircled by water when the Lake was high, and the pavilion was an early site for both the Shawanese post office and the telephone exchange. William Hill’s saltwater taffy was hand-pulled and was a treat for generations of Lake visitors. The Hill family also produced and sold a beautiful pastel colored set of early postcard views of the Lake. Hill added a “photoscape” to the pavilion in 1904 – the first in the region. It was an early “selfie” camera similar to the Polaroid cameras of a much later generation and cost five cents for a photo.

A well-known personality at Inlet was William Hill’s mother, Martha “Grandma” Hill, who maintained a rough wooden stand below the trolley station at the crest of Oneonta Hill. Grandma Hill shared the business with another son, Harry E. Hill. About 1914 the Hills constructed a more substantial home and store near the station. Trolley riders frequently stopped at Hill’s for candy or newspapers before the walk down the hill to the Hotel Oneonta or to the steamboat landing.

With the growing popularity of the Lake as a summer resort, the Inlet, with its proximity to the trolley terminus, had growing importance as a recreational site. In June 1905, John B. Reynolds, Clinton Honeywell, and A. A. Holbrook, who had interests in the trolley line and Hotel Oneonta, erected an eight-lane bowling alley near the Rhoades Hotel.

Despite the growing amusement area at Inlet, it maintained a more leisurely profile from 1905 to 1915 compared to the often raucous Picnic Grounds near Alderson. At the Inlet the Rhoades and Oneonta hotels offered first-class overnight accommodations and served as enjoyable retreats for Wyoming Valley couples seeking an evening dinner and dance. When the Rhoades Hotel was lost to fire in January 1908, the Rhoades tavern, which was a separate facility, was in time converted into a small twenty-room hotel and restaurant. The Inlet hotels apparently enjoyed political favor as they secured liquor licenses while restaurants elsewhere at the Lake only occasionally secured licenses. The absence of a license, however, did not deter the sale of liquor anywhere at the Lake.

For a time in the early 1900’s, a bathhouse and photo gallery were maintained across the bridge near the bowling alley. A carousel was also added for a few seasons. The early bathhouse was later converted to the D. R. Williams restaurant. The Inlet area at the time was a favorite subject of the West Pittston photographer, William J. Harris, who produced a large series of Lake photo views for the booming postscard industry. Harris photographed the majesty of the Hotel Oneonta and the splendor of the steamboats at the Oneonta landing.

Access to the Inlet was along the Old Lake Road from Idetown to the Inlet bridge. Used less often was Carpenter’s Road, which was an extension of the old Worthington Road to the Lake. Hillside was a short road serving the Inlet community, and it originally ran to the Lake alongside the D. R. Williams restaurant next to Hill’s Pavilion.

On the Old Lake Road the principal store was owned by Jacob and Mary Gosart. Jacob Gosart owned a bakery in Luzerne before he married the daughter of A. R. Pembleton who had the Inlet store. Gosart joined Pembleton at the Inlet in 1898 for a couple of years, but then returned to the bakery business in Back Mountain. A familiar sight on the Lake Road in the early 1900’s was Jacob Gosart and his horse-drawn wagon, from which Gosart sold cakes and pies. In 1903 Gosart opened his own store on the Old Lake Road and, about the same time, Pembleton retired from the business.

The 1915 season saw full seasonal use of a beautiful 315 foot long concrete bridge. The new bridge, resting on eleven piers, had been open for use since early December 1914. In 1915 the Shawanese post office moved from Hill’s Pavilion to Gosart’s store on Old Lake Road. By this time the narrow leg between Hill’s Pavilion and the main shore was completely filled with gravel and dirt to prevent flooding. The new concrete bridge ended at Hill’s Pavilion. In 1917 Gosart moved to a more substantial store, now the lot next to Bill’s Café. In the same year William Hill temporarily withdrew from the saltwater taffy business due to ill health. J. Lynn Johnson purchased Hill’s familiar building, and it was renamed Johnson’s Pavilion. But two years later the restaurant would be sold to George Doukakis and renamed the Lakeview.

For a time there was an open-air aeordome (outdoor movie theatre) next to the bowling alley on the Hillside Avenue side. Performances from the Charlie Chaplin era depended on good weather and darkness, and the audience sometimes had to bring pillows and blankets to enjoy the silent movies. During the World War I era, the Hill family leased a section of the Rhoades Hotel plot for a victory garden. When the ground was plowed, a number of Indian artifacts were uncovered. Following the loss of the Hotel Oneonta, the hotel plot attracted a small business and cottage community. The Bon Air restaurant opened on the lakeshore at the steamboat landing in May 1919.

Sunset Pavilion

In November 1919 a 166 foot long shore plot in front of the old bowling alley was purchased by L.C. Schwab of Wilkes-Barre. Leonard C. Schwab (d. 1940) was the meat manager of Sterne’s Market, a high-end grocery store at 16 S. Main Street in Wilkes-Barre. The 5,000 square foot pavilion built by Schwab opened for the three-day Memorial Day weekend in 1920 with Temple Sextette Orchestra. From the dance floor patrons could view the evening sunset across the Lake at West Corner (the later Sandy Beach area). Underneath the pavilion Schwab had bath houses for swimmers, the only bath houses on this side of the Lake. Schwab’s Sunset Pavilion gave its name to the Sunset area – and the Lake front, too, was sometimes called Sunset Beach.

Schwab also opened two refreshment stands and a general store near his pavilion. In August 1921, at the request of young women who were visiting the Lake, Schwab both reduced the admission cost to women at the dances and admitted parents of young women to enter free to insure the propriety of the dances. Cottage people were also granted free afternoon admission to enjoy the pavilion and to receive free dance lessons.

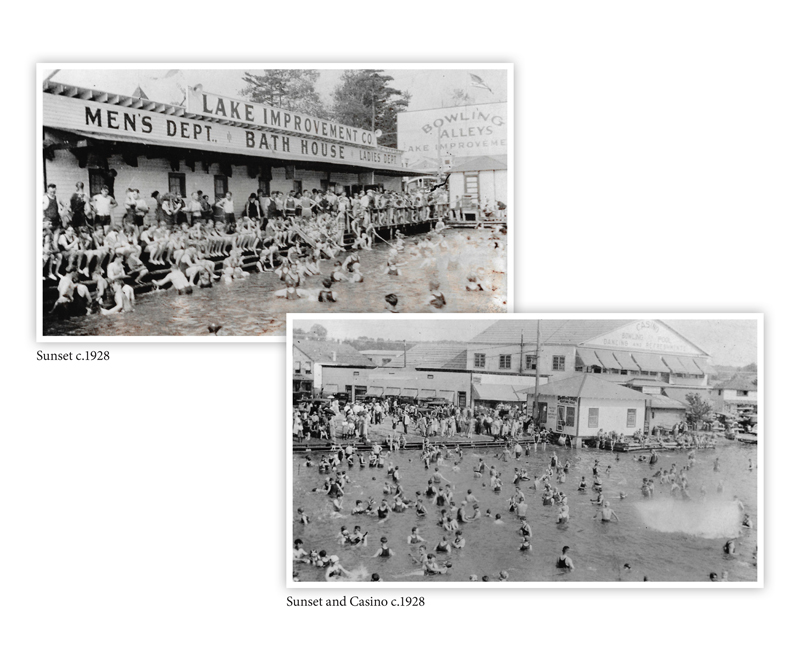

In May 1922 Schwab opened the new season with $10,000.00 in improvements to the Sunset Pavilion. The dance floor was expanded and now reached over the Lake itself. A “sounding board” was built over the orchestra stand which claimed to amplify the music not only within the pavilion but outside over the beach area. Schwab also had an alliance with the new Lake Improvement Company to improve the Sunset beach. A new sand and gravel bottom was laid at the beach. An enclosed bathing area adjacent to the pavilion provided a safe swimming and diving area. The Lake Improvement Company had a 1,000 locker area for swimmers and rented all-wool bathing suits. The reconstructed Sunset Pavilion opened on May 27, 1922, with the Hotel Sterling Orchestra.

Surprisingly, L. C. Schwab sold the Sunset Pavilion in the Spring of 1924 to H. A. Mackie of Mackie Realty Company but it was not publicly announced until November 1924. With the loss of the Oneonta Hotel in early 1919 the Lake had no major hotel. Mackie proposed the pavilion site for a 250 room hotel, built of brick and fireproof, similar to The Breakers, a famed hotel on Atlantic City’s boardwalk. The hotel would have a mezzanine balcony fronting the Lake and along one other side, a modern cafeteria, a roof garden dance floor, a banquet room, and the hotel would be open all year long. Obviously, the hotel was not built.

In late July 1927 seventeen year old Yale Shapiro from Wilkes-Barre dived into a shallow area of the Lake near the pavilion. He struck his head at the bottom. He was unconscious when he was retrieved and a dozen other onlookers gathered in a panic at the site and tumbled into the water. Shapiro died the next day at a hospital.

The landmark Sunset Pavilion was lost in the great fire of 1929. The pavilion’s supporting cribbing still lies under the waters of the Lake and were once a common site to view by patrons of Tommy O’ Brien’s scuba-diving rental service at Sunset.

Lake Improvement Company

The massive development of Sunset occurred after George W. Bennethum created the Lake Improvement Company in January 1922. His partners were George H. Kline and George B. Martin. Bennethum purchased numerous lots at Sunset, and within a short time, he erected several other structures at Sunset while also improving the Lake’s shoreline for swimming. He purchased fifteen World War I barracks from Cape May, New Jersey. He reassembled them along Hillside Avenue behind the Grotto area. They were named after the states and were popularly called the “state cottages,” although Bennethum advertised the area as Bungalow City. A cottage rented for fifty dollars weekly or $175.00 monthly.

The Lake Improvement Company either acquired the earlier bowling alley at Sunset or built a new one. It managed the beach area. There were ice houses to sell ice to the general public and for its own operation. There were gas stations and accessory stores. The company also had “open-air” movies at night which were free to the public. A beauty shop was added for women. The beach was illuminated for night swimming.

During the three-month Lake season in 1922 the Lake was patrolled by Police Chief Frank Stutz joined by Patrolmen Arthur Smith and John Feasler. The latter was on-leave from the Wilkes-Barre City police force.

G. W. Bennethum was a native of Southeastern Pennsylvania where he was a widely-known promoter of movie theaters and vaudeville shows. He owned theaters in Pottstown, Allentown, Boyertown, Coatesville, Quakertown and others in Maryland. He also was a partner in the forty theatre Orpheum circuit. In April 1927 he would pass away in Hot Springs, Arkansas, at age 49.

The Lake Improvement Company stimulated the rapid development of Sunset. Carpenter’s Hotel was a popular dinner site that provided chicken dinners for one dollar. The Bon Air restaurant, at the steamboat landing, was completely remodeled in 1922 by new managers, Charles Groh and William Reiger. To encourage summer traffic, Thomas Pugh ran a private bus line every afternoon from Wilkes-Barre to the Lake. Pugh also owned an icehouse near the Sunset bridge for the convenience of area cottagers. There were other Sunset shops for the summer crowd. At the Sunset Pavilion, George Fannick had a barber shop and Ace Hoffman also had eight-hour film developing service. Hoffman also produced a series of photo postcard views of the Lake.

The Belmont Quick Lunch, owned by Mildred Dunn, was next to a New Oneonta Pavilion. Petett’s Inn and Kanner’s meat market were on the Old Lake Road along with Gosart’s store, where three different brands of gasoline were sold. Fireworks for the July 4 holiday were available from Walko’s store at the steamer landing. Bennethum’s Lake Auto Bus Company met passengers at the trolley station from early in the morning to midnight and provided bus service around the Lake. Next to the Inlet basin, Bennethum built a large public garage, which later was the site of Sunset Bingo. Bennethum acquired the garage building from the government when he purchased the “state cottages.” He originally placed it at the top of Oneonta Hill, but the garage business there was unsuccessful and he moved it to Sunset.

New Oneonta Pavilion

With the emerging jazz-age, the historic site of the Hotel Oneonta would become one of the region’s most popular dance halls. Following the loss of the Hotel Oneonta, lots were laid out on the Oneonta plot. Two lots at the bottom of the Oneonta Hill at the intersection with the Lake road were purchased in 1921 by Ted Pringos, who had a restaurant at Sunset. At the same time, a group of businessmen in Wilkes-Barre saw the site as ideal for a new dance pavilion. The Oneonta Amusement Company was formed by Harry Rosentel, James J. McKane, Charles Thoman, Charles Gallagher and Ted Pringos. They engaged the respected Amos Kitchen, a Harvey’s Lake building contractor, to build the beautiful New Oneonta Pavilion on the Pringos lots.

The cabaret dance hall on the second floor of the New Oneonta Pavilion was one hundred feet long and twenty feet wide. Seating areas were on front extensions at both ends of the dance floor. On the left side of the ground floor of the pavilion was a restaurant, and on the right was a beauty salon behind which a soda fountain faced the Oneonta Hill road. Opening night was May 27, 1922, with Kilgore’s Orchestra. Dances were usually held five evenings a week with Wednesday and Saturday nights the largest draws. The better bands of the area played at the New Oneonta Pavilion, especially Harry MacDonald’s Californians, always a crowd-pleaser. Among the players with MacDonald’s was Russ Morgan of Nanticoke, who later had his own nationally renowned dance band. Other famous bands that played at the New Oneonta Pavilion were Wayne King, popularly known as the “Waltz King,” and Paul Whiteman, who played three times at the Oneonta Pavilion.

At the same time, other promoters were drawn to Sunset. Frank Devlin, owner of the Family Theatre in Wilkes-Barre bought Wright’s Lakeside cottage in 1919. He then purchased shoreline lots near the Sunset bridge where he built the Casino in the spring of 1924. The Casino, featuring the largest bowling alley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, opened Memorial Day 1924. Billiards and whirl ‘o ball provided entertainment, and a dining room or refreshment parlor accommodated 250 people. The whirl ‘o ball was a form of miniature bowling. Individual players sought to roll a ball down a twenty-foot alley into a center or side pockets to score points. The nickel game automatically returned the ball for the next attempt. On the first floor there was a gift shop and grocery store; on the second floor of the Casino was a large dance hall.

The Grotto

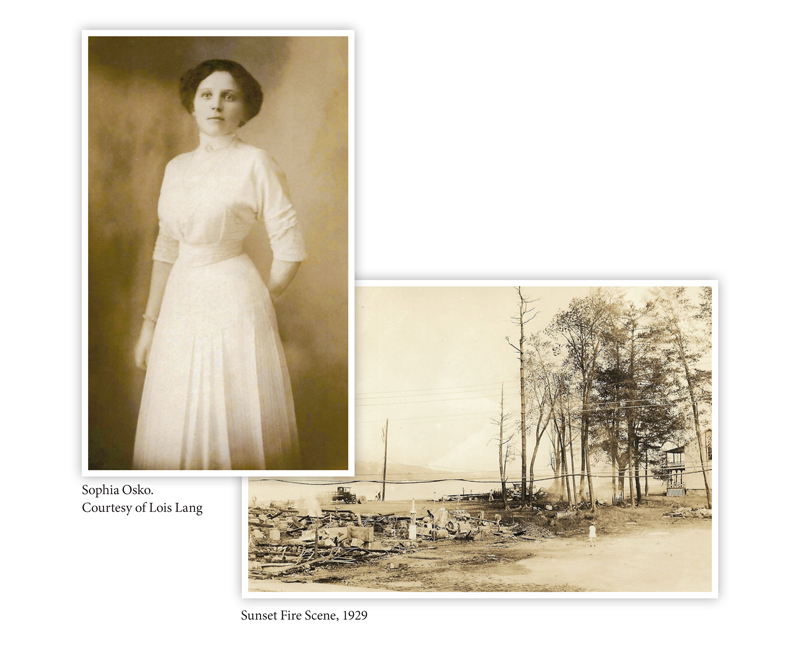

The Grotto name has been associated with Sunset since the early 1920s. The Grotto Cote D’Asur restaurant was opened in mid-June 1922 by partners Sophia Oskierko, Stella E. Starr and Helen Ambrose. Oskierko was generally known as Sophia Osko. The name Cote D’Asur is likely a version of Cote d’Azur, the famous coastline of the French Riviera of southeast France on the Mediterranean Sea. Located at the rear of the Bennethum bowling alley, its specialty was a chicken and waffle dinner. But it also served sea food and steak dinners and the restaurant was open year-round.

Two strands of Sunset development emerged from the Cote D’Asur: The Cotton Club and the New Grotto.

The Cotton Club

In July 1924 the Grotto Cote D’Asur site was reformed as the White Birch restaurant by Edward Ambrose and Stanley “Stogie” Stogski. By June 1930 it was available to lease as the Paloma Inn and emerged as the Cotton Club in September 1930, a local version of the famous Cotton Club in New York City’s Harlem. The Lake’s Cotton Club would become Sunset’s best known site for the next two decades. It engaged a six-piece Black Orchestra with dancing every evening and was open throughout the year. For New Year’s Eve on December 31, 1932, the club had three different evening shows. Admission and a turkey dinner was six dollars a couple. Competition came from Sunset’s Plantation Club at seven dollars a couple but with Helen Morgan’s “Hot Cha” Beauties and various radio acts from the Silver Slipper club in New York City and music by a New York City band.

In June 1931 the Cotton Club retained a house band “Pete and His Honey Boys.” Pete Peterson was an accomplished piano player from Wilkes-Barre. His band would accompany out-of-town acts at the club. The Cotton Club band roomed at the Adam Smith boarding house at Sunset. On June 20, 1931, the Cotton Club featured the Hillman Brothers, a famous Black vaudeville tap-dance act. George I. Hillman and Christopher Hillman would continue their dance act for decades touring with the USO, Bob Hope and Tony Bennett. George Hillman appeared in Broadway shows from 1968 to 1981, and at age 86 was featured in the dance documentary “Black and Blue.” He died in 1995, one year after his brother Christopher.

Pete Peterson played several years at the Cotton Club. Among his orchestra players were Bill Sorber, clarinet and sax wizard, formerly with the Cliff Jackson orchestra; Jim McLeary, trumpet player, from the Cab Calloway orchestra; and Alfred Thomas, trombonist, from the Elmer Snowden Small Paradise orchestra, all three from New York City.

By 1935 Pete Peterson had a thirty minute radio show on Saturday evenings at 6:00 P.M. on WBAX. By 1937 Peterson’s band was playing at various Wyoming Valley venues and in the 1940s Peterson, known as the “King of the Ballads” was a solo pianist at Williams Bar-B-Q on Butler street in Wilkes-Barre.

In the meantime, the Cotton Club featured Blanche Calloway, sister of famed Cab Calloway, radio and screen star and conductor, in June 1936. In the same year the club opened another Cotton Club in Hanover Township but it had less success.

On the last Sunday in May 1937 the Cotton Club was charged by Harvey’s Lake police with violation of selling liquor contrary to Sunday closing laws. The police found 152 people in the bar who were served liquor. In the mid WWII period Stanley Stognoski relinquished his lease and liquor license to the Cotton Club and Helen Ambrose, the property owner, managed the club.

Over the years the Lake’s Cotton Club grew more traditional with a greater emphasis on dinners and banquets and in June 1945 it announced a new 40-foot stone bar. While dance music was still offered the Cotton Club would partially close for the winter season. After Labor Day it was only opened on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday until New Year’s Eve. The Cotton Club became the Circle Inn in mid-1949.

The New Grotto

The Grotto is the story of Sophia Osko. Her original Grotto Cote D’Asur evolved into the Cotton Club, but when she surrendered management of the Grotto Cote D’Asur in early 1924 she and Stella Starr established the New Grotto restaurant next to the Casino at the Sunset bridge. Within three months Osko and Starr, along with 13 other Lake vendors, were charged by the Harvey’s Lake Protective Association and Lake Police Chief J. L. Ruth with violation of liquor and gambling laws. In any event, the New Grotto continued business and was only slightly damaged in the August 1928 fire at Sunset.

The New Grotto specialized in a 75 cent “blue plate” dinner of chicken, beef, pork or veal, or a one dollar half-chicken dinner. For New Year’s Eve on December 29, 1930, the New Grotto was open from 10 P.M. to 5 A.M. The Memphis Stompers provided music and admission with a turkey dinner was five dollars a couple. In May 1931 Stella Starr broke with Osko and Starr opened the Topsail Manor restaurant on Old Lake Road but it lasted only one year.

In 1931 Osko recast the New Grotto as the Hollywood Club. But the club was charged with liquor violations in October 1931 in a State Police raid. In March 1932 any sentence was suspended since Osko agreed to close the Hollywood Club. Later in the year Osko reopened the site as Osko’s Grill. In the meantime in late 1934 Osko also assumed management of the Wilkes Hotel on North Main street, one block from Public Square. By 1935 Osko resumed the New Grotto name for her restaurant and in May 1936 she advertised her fourteenth anniversary as owner of the Grotto name.

By 1939, however, Sophia Osko and now husband Oliver Burke, Jr., had new plans for a restaurant at the Lake. The New Grotto was now managed by Jack Nothoff. Later in the War years Nothoff left the New Grotto to open his own bar which would later became the Villa Roma. For the balance of World War II Osko and Burke resumed management of the New Groto but selling it to Joseph and Bertha DiCarlo in November 1945.

Post-War the New Grotto had nightly dancing from 9 PM to 1 AM and was renovated in 1947 to feature floor shows and musical acts. In late August 1947 Marty Bannon performed at Burke’s Grotto. Bannon was known as the “Al” Jolson of the Wyoming Valley.

In the meantime in December 1940 Sophia Osko and Oliver Burke, Jr., would acquire the property which became Burke’s Bar-B-Cue across from the old Sunset Pavilion site. This site in more recent years has had a succession of restaurant names including Damien’s on the Lake, Dominic’s on the Lake, Boathouse Bar and Grille, and Jonathan’s.

In October 1947 Joseph Stuccio, a Nanticoke pizza maker, acquired the New Grotto site and combined dining, pizza, and music at Sunset. Stuccio’s grand opening was Thursday, July 1, 1948, with music by Men of Note. On Friday, May 20, 1949, Stuccio opened his Lake restaurant for the new season simply as the “Grotto.”

The continuation of the Grotto story is discussed in the Afterword.

In the mid 1920s the merchants at the Sunset area, under the spur of the Lake Improvement Company, aggressively advertised Sunset attractions and provided furious competition for the Picnic Grounds. A number of roadside and beach stands, a gasoline station, and other recreational conveniences were managed or leased by the Lake Improvement Company at Sunset. The company also published its own series of postcard views of Sunset. Conveniently situated near the Oneonta trolley station, Sunset had a special attraction for crowds drawn to swimming and dancing. For the 1925 season Bennethum expanded the beach area with additional cribbing; a long swimming dock was built in the water from the Sunset Pavilion almost to the Inlet bridge. The Lake Improvement Company built a bathhouse over the water next to the Sunset Pavilion; the company rented Jensen all-wool bathing suits to Sunset swimmers.

In November 1924 a fire of uncertain origin began in a vacant Sunset cottage called the Fern Club. The fire spread and was battled by the Lake, Luzerne and Kingston fire departments. The fire departments exhausted the well of the Dodge Inn for water to contain the fire even as the fire threatened both the Dodge and White Birch hotels. Nine cottages were lost in the fire. The following March 1925 the Dodge Inn and Cliff Edwards cottages were destroyed in another fire.

In 1926 the Sunset Pavilion was managed by J. B. Reilly, but it was suffering from dance-hall competition. Its dance admissions, even at thirty-five cents for women and fifty cents for men, could not compete with the glamour of the seventy-five cent dances and name bands at the New Oneonta Pavilion. For a time the Sunset Pavilion would try roller skating, but the change was not very successful. Additional amusement competition at the Lake was also underway at Sandy Beach, which had opened a year earlier.

By 1926 the long concrete bridge was deteriorating rapidly due to winter ice damage. The county decided to build a short concrete bridge at Sunset. Additional filling of the Inlet basin occurred to build the shorter replacement bridge at Sunset, which was opened in 1928.

The 1928 Fire

On Sunday, June 24, 1928, a disastrous fire began to signal the end of a decade of phenomenal growth at Sunset. In the early morning, Willard Gosart, the night watchman for the new county bridge, discovered a fire in the lower story of the Belmont restaurant next to the New Oneonta Pavilion. Esther Ide, the night operator of the Commonwealth Telephone exchange, signaled area cottagers to help fight the fire. Despite a steady rain, the fire spread rapidly from the restaurant to the New Oneonta Pavilion and surrounding structures. Earlier in the year, the New Oneonta Pavilion had been remodeled. A spacious veranda had been added on the lower floor, and the upper floor had been enclosed for year-round use.

After the fire call, Sen. A. J. Sordoni, with the Lake pumper, was the earliest to arrive, followed by the Kingston Independent Hose Company, which made the run to the Lake in twenty minutes. Rescuers smashed into the rear apartment of the dance pavilion to arouse James Hennihan and Albert Mason who were sleeping in the pavilion’s apartment. Hennihan was a local prize fight referee who had assumed the management of the pavilion for the 1928 season; he had finished his first dance only hours earlier. The flames were furious, and four times the firemen had to douse flames that even threatened the Lake pumper, which stood near the steamboat landing. Rowland Newsbigle, one of the fire-fighters, was forced to jump into the Lake at avoid the snapping electric wires. By 6:00 P.M. the fire was under control. Lost were the reconstructed New Oneonta Pavilion, the Belmont restaurant, Mundy’s candy store and cottages, May Gill’s Bridge restaurant and the Hochreiter cottage.

There was inadequate insurance to rebuild the dance hall, and the Oneonta Amusement Company went into insolvency. The Oneonta dance site was eventually sold to the Commonwealth Telephone Company for its large exchange building. A few stone steps from the New Oneonta Pavilion still grace the property.

Within two months after the loss of the New Oneonta Pavilion, another fire at Sunset had tragic results. On August 16, 1928, a fire broke out in the rear of the Casino bowling alley at 7:30 A.M. In the rear of the building was a boarding area for pinboys. Eight pinboys were aroused and escaped through the efforts of Andrew Kovatch, the Casino bowling manager. But as the boys were escaping the blinding smoke and heat, two of the eight teenage boys, Abraham Dymond and Matthew Yatko, apparently retreated to their room where they suffocated. The fire had started in the kitchen, to the left of the boys’ bedroom. An oil stove had been started an hour before the fire. There were severe damages to the rear of the Casino and water damage to eight bowling alleys. The Grotto restaurant next door received slight damage by fire and water.

The Great Fire 1929

The following year, on August 26, 1929, the Lake experienced its greatest property loss in history to fire. Ten buildings between Hillside Avenue and Carpenter Road, which comprised most of the amusement section, were destroyed in a three-hour inferno. In the late afternoon, a fire started in the power plant of the Bennethum bowling alley. Fire extinguishers could not contain the blaze, and the flames shortly destroyed an adjoining boarding house used by the Bennethum employees. The bowling alley itself caught fire, and the flames spread to an adjoining store and office building. Fanned by a strong wind, the flames jumped the thirty-five foot front drive to the Sunset Pavilion and the Lake Improvement Company bathhouse. Dorothy Gunton, the telephone exchange operator, called local fire departments and then fled the exchange as fire enveloped the building cutting all telephone service from the area.

All of Sunset was at risk in the fire. In a remarkable performance, Sen. A. J. Sordoni directed the sixty fire-fighters as they struggled to contain the huge blaze that was destroying Sunset. The firemen directed their hoses on the Grotto, Casino and Bungalow City near the bridge. They also saved the White Birch Inn and Carpenter’s Hotel on the opposite side of the disaster. As President of the Harvey’s Lake Light Company, Sordoni summoned four gangs of linemen. They cut the wire service to the area and rewired the lines around the fire zone, restoring light service to the area in forty-five minutes. Sordoni was also President of the Commonwealth Telephone Company, and he had the company’s general manager, R. W. Kentzer, rushed to the scene; in an hour a line to the Valley was opened. In less than six hours a new exchange and switchboard was in operation. Two Bell Telephone Company operators, Audrey Healtherly and Jean Hommick, were vacationing at the Lake. As they were observing the fire, they were pressed into volunteer service to manage the Commonwealth lines.

The fire damages totaled $135,000.00, a devastating loss by the standards of the time. George Bennethum did not witness the disaster. The energetic developer died suddenly in April 1927, and the Sunset holdings were now managed by Estelle Bennethum. The Bennethum estate suffered the greatest loss in the fire. The bowling alley, candy store, office boarding house, warehouse and power plant were totally destroyed. The Sunset Pavilion and Bennethum bathhouse were also destroyed, along with a building that contained the telephone exchange and Garinger meat market. A restaurant on the Lake Road, owned by Thomas James, was also lost. Damaged in the fire was the saltwater taffy stand of William Hill, who had a small stand along the Lake shore above the Sunset Pavilion. He had retired a few years earlier from Hill’s Pavilion at the bridge. Before the fire, however, William Hill had renewed his popular saltwater taffy trade, which was a tradition at the Lake for four decades. Despite the fire, both Hill brothers, William and Harry, continued their family trade and reopened stands at Sunset.

A Post-Fire Perspective

The Bennethum Estate limited its rebuilding at Sunset, although the area continued as a popular recreation site for nearly three more decades. Estelle Bennethum acquired a pavilion at the top of Oneonta Hill and used it for the reconstruction of the Lakeview Restaurant along the Lake front. Bennethum’s 1925 Lakeview restaurant at Sunset had a unique history. The Old Lake Road was the public access entrance to Sunset. At the end of the road the bridge was on the right and the Lakeview on the far end of the bridge. It was initially leased to George Doukakis but in September 1931 it became the Plantation Club featuring a mix of Broadway, Harlem and Dixieland music. Created by Jack Laurie and Hubby Pesavento, they had created the earlier Cotton Club, but now sought to manage a competing night club. The venture lasted two years.

In 1933 Wyoming Valley’s best-known photographic studio owner, Ace Hoffman, leased the Plantation Club. He would also operate the Airport Inn at the Forty-Fort Airport. Years earlier Ace Hoffman operated a photo studio at the Sunset Pavilion. A publicity master Hoffman held a contest to re-name the Plantation Club. Of course, the contest winner suggested the name “Ace Hoffman’s.” Hoffman was charged with selling beer on a Sunday later in the year, a violation of State liquor law. Hoffman claimed he was not selling beer on Sunday; he was selling pretzels which came with a free beer. Judge W. S. McLean found Hoffman not guilty. Hoffman’s restaurant lasted eighteen months before it reverted to the Bennethum Estate and recast in October 1934 as the LaCasa – a Sunset landmark for four decades.

For a number of years after the 1929 fire the Bennethum Estate continued to manage the family’s Sunset holdings, including La Casa, the restaurant at the end of the bridge. The Casino, too, remained a popular attraction at Sunset, providing bowling, pool, dancing and refreshments. There was an extensive dock system for Sunset swimmers; it encircled the beach from the site of the old Sunset Pavilion to the bridge. There were two high diving boards on the docks. On the beach in front of the Casino was a bathhouse for men and women along with refreshment and novelty stands. During the 1930’s the swimming area was known as Crystal Beach.

Almost the entire history of Sunset to this time was witnessed with bemusement by a unique Sunset institution, the Oxford educated Ed Swan, who had rented rowboats at the Inlet for nearly half a century. Swan immigrated to the United States from England as a young man. He was originally associated with W. W. Finch, who had rented rowboats on the Susquehanna at Wilkes-Barre since 1881. During the 1880’s Swan began a rowboat rental service at the Lake. Originally, his boats were located on the Lake shore near the Rhoades Hotel, but the Lake waves damaged his boat line. Swan then relocated his service to the Inlet basin. Swan’s shack along the Inlet shore was filled with a tumbling collection of junk, but it was a special place for friends to idle away time and to watch the seasons turn, until Ed Swan’s time also passed in 1933.

In later years, the Sunset area would experience great change and new summer institutions would emerge. A summer dwelling across from Harry Hill’s candy stand would be converted into Sophia Osko Burke’s new restaurant. Carpenter’s Hotel would become the tearoom of Kitty Walsh followed by Sloppy Tony’s night club. The Cotton Club would eventually acquire the names Circle Inn and Top Shelf under the ownership of Peter Ambrose, and under later owners it would have the names Scarlet’s Inn and Flagstone House. Carpenter’s Road would gradually be filled with a large cottage community and the “state cottages” would provide summer rentals well into the modern period. A significant change in the appearance of Sunset occurred with the construction of the new Lake highway from Idetown to Sunset in 1941. Filling of the Inlet basin also contributed to the changed appearance of the area. The Bennethum holdings were eventually acquired by other interests, particularly Francis and Peter Ambrose who helped charter the development of Sunset during the modern era.

More than nine decades have passed since the destructive fire of 1929. Sunset’s appearance has changed dramatically over the years. It now hosts a modern Grotto restaurant and a condominium community and a new 2016 bridge. A considerably smaller Inlet basin provides slip rentals for boaters. The La Casa and Casino are vague memories but on any day one can stand at Sunset and imagine a wonderfully short time in the 1920s when Sunset was in its glory.

Leave a comment